On December 9th, at NIPS 2015, I met two engineers from SoundCloud, which is not only providing unsigned artists a venue to get their music heard (and commented on), and providing recommendation and music-oriented social networking, but also, if I understand correctly, is interested in content analysis for various purposes. Some of those have to do with identifying work that may not be original, which can range from quotation to plagiarism (the latter being an important issue in my line of work: education), but also involve the creation of derivative content, like remixing, to which they seem to have a healthy approach. (At the same event, the IBM Watson program director also suggested that they could conceivably be interested in generative tools based on music analysis.)

I got interested in clave-direction recognition to help musicians, because I was one, and I was struggling—clave didn’t make sense. Why were two completely different patterns in the same clave direction, and two very similar patterns not? To make matters worse, in samba batucada, there was a pattern said to be in 3-2, but with two notes in the first half, followed by three notes in the second half. There had to be a consistent explanation. I set out to find it. (If you’re curious, I explained the solution thoroughly in my Current Musicology paper.)

However, clave is relevant not just to music-makers, but to informed listeners and dancers as well. A big part of music-in-society is the communities it forms, and that has a lot to do with expertise and identity in listeners. Automated recognition of clave-direction in sections of music (or entire pieces) can lead to automated tagging of these sections or pieces, increasing listener identification (which can be gamified) or helping music-making.

My clave-recognition scheme (which is an information-theoretically aided neural network) recognizes four output classes (outside, inside, neutral, and incoherent). In my musicological research, I also developed three teacher models, but only from a single cultural perspective. Since then, I have recently submitted a work-in-progress and accompanying abstract to AAWM 2016 (Analytical Approaches to World Music) about what would happen if I looked at clave direction from different cultural perspectives (which I have encoded as phase shifts), and graphed the results in the complex plane (just like phase shift in electric circuits).

Another motivating idea came from today’s talk Computational Principles for Deep Neuronal Architectures by Haim Sompolinsky: perceptual manifolds. The simplest manifold proposed was line segments. This is poignant to clave recognition because among my initial goals was extending my results to non-idealized onset vectors: [0.83, 0.58, 0.06, 0.78] instead of [1101], for example. The line-segment manifold would encode this as onset strengths (“velocity” in MIDI terminology) ranging from 0 (no onset) to 1 (127 in MIDI). This will let me look inside the onset-vector hypercube.

Another tie-in from NIPS conversations is employing Pareto frontiers with my clave data for a version of multi-label learning. Since I can approach each pattern from two phase perspectives, and up to three teacher models (vigilance levels), a good multi-label classifier would have to provide up to 6 correct outputs, and in the case that a classifier cannot be that good, the Pareto frontier would determine which classifiers are undominated.

Would all this be interesting to musicians? Yes, I think so. Even without going into building a clave-trainer software into various percussion gear or automated-accompaniment keyboards, this could allow clave direction to be gamified. Considering all the clave debates that rage in Latin-music-ian circles (such as the “four great clave debates” and the “clave schism” issues like around Giovanni Hidalgo’s labeling scheme quoted in Modern Drummer*), a multi-perspective clave-identification game could be quite a hit.

So, how does a Turkish math nerd get to be obsessed by this? I learned about clave—the Afro-Latin (or even African-Diasporan) concept of rhythmic harmony that many people mistake for the family of fewer than a dozen patterns, or for a purely Cuban or “Latin” organizational principle—around 1992 from the musicians of Bochinche and Sonando, two Seattle bands. I had also grown up listening to Brazilian (and Indian, Norwegian, US, and German) jazz in Turkey. (My first live concert by a foreign band was Hermeto Pascoal e Grupo, featuring former CBC faculty Jovino Santos Neto.) So, I knew that I wanted to learn about Brazilian music. (At the time, most of what I listened to was Brazilian jazz, like Dom Um Romao and Airto, and I had no idea that they mostly drew from nordestino music, like baião, xote, côco, and frevo**―not samba).

Fortunately, I soon moved to Portland, where Brian Davis and Derek Reith of Pink Martini had respectively founded and sustained a bloco called Lions of Batucada. Soon, Brian introduced us to Jorge Alabê, and then to California Brazil Camp, with its dozens of amazing Brazilian teachers. . . But let’s get back to clave.

I said above that clave is “the Afro-Latin (or even African-Diasporan) concept of rhythmic harmony that many people mistake for the family of fewer than a dozen patterns, or for a purely Cuban or ‘Latin’ organizational principle.” What’s wrong with that?

Well, clave certainly is an organizational principle: It tells the skilled musician, dancer, or listener how the rhythm (the temporal organization, or timing) of notes in all the instruments may and may not go during any stretch of the music (as long as the music is from a tradition that has this property, of course).

And clave certainly is a Spanish-language word that took on its current meaning in Cuba, as explained wonderfully in Ned Sublette’s book.

However, the transatlantic slave trade did not only move people (forcefully) to Cuba. The Yorùbá (of today’s southwest Nigeria and southeast Benin), the Malinka (a misnomer, according to Mamady Keïta for people from Mali, Ivory Coast, Burkina Faso, Gambia, Guinea, and Senegal), and the various Angolan peoples were brought to many of today’s South American, Caribbean, and North American countries, where they culturally and otherwise interacted with Iberians and the natives of the Americas.

Certain musicological interpretations of Rolando Antonio Pérez Fernández’s book La Binarización de los Ritmos Ternarios Africanos en América Latina have argued that the organizational principles of Yoruba 12/8 music, primarily the standard West African timeline (X.X.XX..X.X.X)

and the Malinka/Manding timelines met the 4/4 time signatures of Angolan and Iberian music, and morphed into the organizational timelines of today’s rumba, salsa, (Uruguayan) candombe, maracatu, samba, and other musics of the Americas.

Some of those timelines we all refer to as clave, but for others, like the partido-alto in Brazil***, it is sometimes culturally better not to refer to them as clave patterns. (This is understandable, in that Brazilians speak Portuguese, and do not always like to be mistaken for Spanish-speakers.)

Conceptually, however, partido-alto in samba plays the same organizational role that clave plays in rumba and salsa, or the gongue pattern plays in maracatu: It immediately tells knowledgeable musicians how not to play.

In my research, I found multiple ways to look at the idiomatic appropriateness of arbitrary timing patterns (more than 10,000 of them, only about a hundred of which are “traditional” [accepted, commonly used] patterns). I identified three “teacher” models, which are just levels of strictness. I also identified four clave-direction categories. (Really, these were taught to me by my teacher-informers, whose reactions to certain patterns informed some of the categories.)

Some patterns are in 3-2 (which I call “outside”). While the 3-2 clave son (X..X..X…X.X…):

is obvious to anyone who has attempted to play anything remotely Latin, it is not so obvious why the following version of the partido-alto pattern is also in the 3-2 direction****: .X..X.X.X.X..X.X

Some patterns are in 2-3 (which I call “inside”). Many patterns that are heard throughout all Latin American musics are clave-neutral: They provide the same amount of relative offbeatness no matter which way you slice them. The common Brazilian hand-clapping pattern in pagode, X..X..X.X..X..X. is one such pattern:

It is actually found throughout the world, from India and Turkey, to Japan and Finland, and throughout Africa; from Breakbeats to Bollywood to Metal. (It is very common in Metal.) The parts played by the güiro in salsa and by the first and second surdos in samba have the same role: They are steady ostinati of half-cycle length. They are foundational. They set the tempo, provide a reference, and go a long way towards making the music danceable. (Offbeatness without respite, as Merriam said*****, would make music undanceable.)

Here are some neutral patterns: X…X…X…X… (four on the floor, which, with some pitch variation, can be interpreted as the first and second surdos):

….X.X…..X.X. (from ijexá):

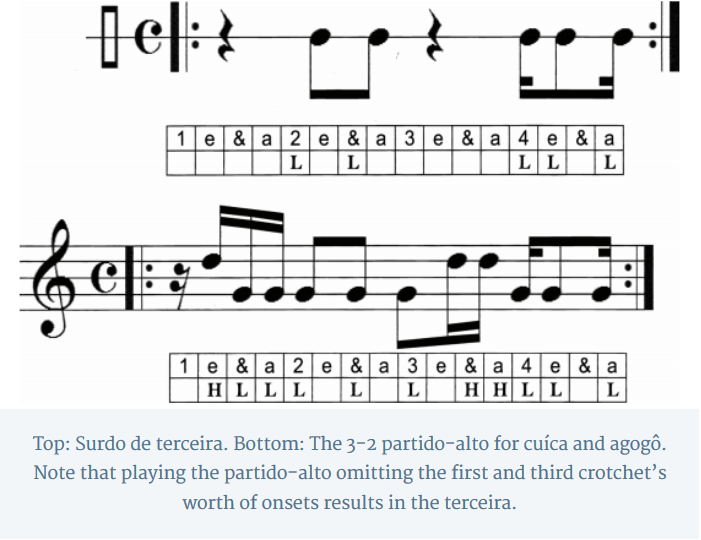

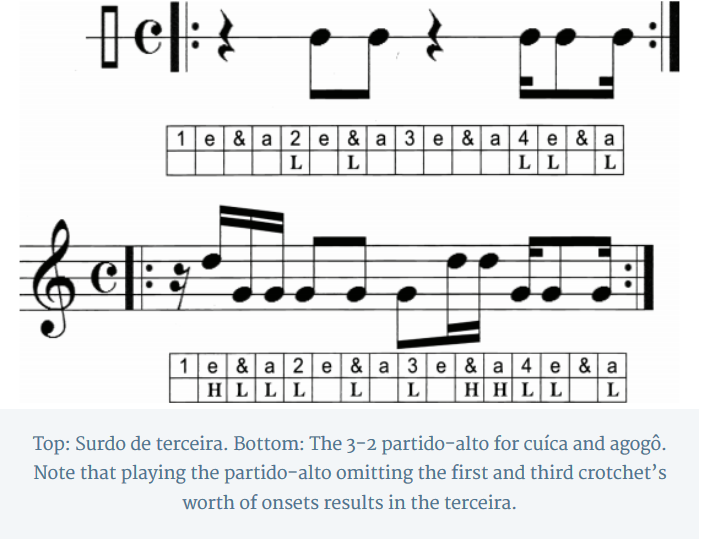

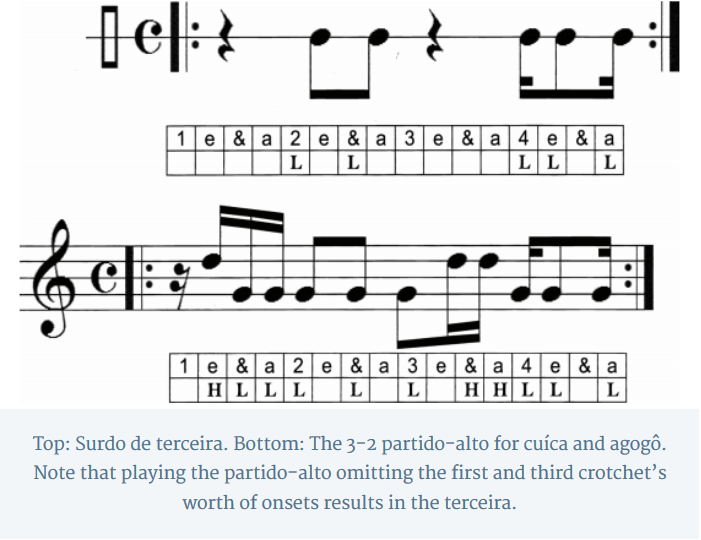

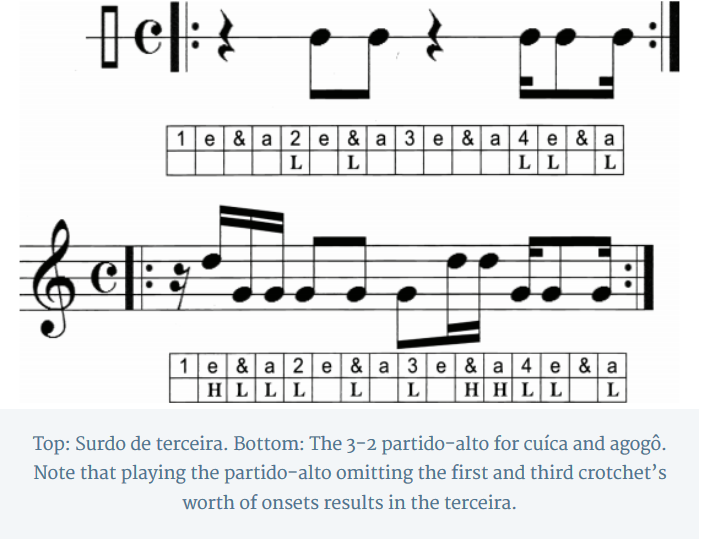

and XxxXXxxXXxxXXxxX. (This is a terrible way to represent swung samba 16ths. Below is Jake “Barbudo” Pegg’s diagrams, which work much better.)

The fourth category is incoherent patterns. These are patterns that are not neutral, yet do not conform to either clave direction, either. (One of my informers gave me the idea of a fourth category when he reacted to one such pattern by making a disgusted face and a sound like bleaaahh.)

A pattern that has the clave property immediately tells all who can sense it that only patterns in that clave direction and patterns that are clave-neutral are okay to play while that pattern (that direction) is present. (We can weaken this sentence to apply only to prominent or repeated patterns. Quietly passing licks that cross clave may be acceptable, depending on the vigilance level of the teacher model.)

So, why mention all this right now? (After all, I’ve published these thoughts in peer-reviewed venues like Current Musicology, Bridges, and the Journal of Music, Technology and Education.)

For one thing, those are not the typical resources most musicians turn to. Until I can write up a short, highly graphical version of my clave-direction grammar for PAS, I will need to make some of these ideas available here. Secondly, the connection to gamification and musical-social-networking sites, like SoundCloud, are new ideas I got from talking to people at the NIPS reception, and I wanted to put this out there right away.

FOOTNOTES

* Mattingly, R., Modern Drummer, Modern Drummer Publications, Inc., Cedar Grove, NJ, “Giovanni Hidalgo-Conga Virtuoso,” p. 86, November 1998.

** While talking to Mr. Fereira of SoundCloud this evening at NIPS, he naturally mentioned genre recognition, which is the topic of my second-to-last post. (I argued about the need for expert listeners from many cultural backgrounds, which could be augmented with a sufficiently good implementation of crowd-sourcing.) I think he was telling me about embolada, or at least that’s how I interpreted his description of this MC-battle-type of improvised nordeste music. How many genre-recognition researchers even know where to start in telling a street-improvisation embolada from even, say, a pagode-influenced axé song like ‘Entre na Roda’ by Bom Balanço? (Really good swing detection might help, I suppose.)

*** This term has multiple meanings; I’m not referring to the genre partido-alto, but the pattern, which is one of the three primary ingredients of samba, along with the strong surdo beat on 2 (and 4) and the swung samba 16ths.

**** in the sense that, in the idiom, it goes with the so-called 3-2 “bossa clave” (a delightful misnomer): X..X..X…X..X..,

as well as with the rather confusing (to some) third-surdo pattern ….X.X…..XX.X,

as well as with the rather confusing (to some) third-surdo pattern ….X.X…..XX.X,

which has two notes in its first half, and three notes in its second half. (Yes, it’s in 3-2. My grammar for clave direction explains this thoroughly. [http://academiccommons.columbia.edu/catalog/ac:180566])

***** See Merriam: “continual use of off-beating without respite would cause a readjustment on the part of the listener, resulting in a loss of the total effect; thus off-beating [with respite] is a device whereby the listeners’ orientation to a basic rhythmic pulse is threatened but never quite destroyed” (Merriam, Alan P. “Characteristics of African Music.” Journal of the International Folk Music Council 11 (1959): 13–19.)

ALSO, I use the term “offbeatness” instead of ‘syncopation’ because the former is not norm-based, whereas the latter turns out to be so:

Coined by Toussaint as a mathematically measurable rhythmic quantity [1], offbeatness has proven invaluable to the preliminary work of understanding Afro-Brazilian (partido-alto) clave direction. It is interpreted here as a more precise term for rhythmic purposes than ‘syncopation’, which has a formal definition that is culturally rooted: Syncopation is the placement of accents on normally unaccented notes, or the lack of accent on normally accented notes. It may be assumed that the norm in question is that of the genre, style or cultural/national origin of the music under consideration. However, in all usage around the world (except mine), normal accent placement is taken to be normal European accent placement [2, 3, 4].

For example, according to Kauffman [3, p. 394], syncopation “implies a deviation from the norm of regularly spaced accents or beats.” Various definitions by leading sources cited by Novotney also involve the concepts of “normal position” and “normally weak beat” [2, pp. 104, 108). Thus, syncopation is seen to be norm-referenced, whereas offbeatness is less contextual as it depends solely on the tactus.

Kerman, too, posits that syncopation involves “accents in a foreground rhythm away from their normal places in the background meter. This is called syncopation. For example, the accents in duple meter can be displaced so that the accents go on one two, one two, one two instead of the normal one two, one two” [4, p. 20; all emphasis in the original, as written]. Similarly, on p. 18, Kerman reinforces that “[t]he natural way to beat time is to alternate accented (“strong”) and unaccented (“weak”) beats in a simple pattern such as one two, one two, one two or one two three, one two three, one two three.” [4, p. 18]

Hence, placing a greater accent on the second rather than on the first quarter note of a bar may be sufficient to invoke the notion of syncopation. By this definition, the polka is syncopated, and since it is considered the epitome of “straight rhythm” to many performers of Afro-Brazilian music, syncopation clearly is not the correct term for what the concept of clave direction is concerned with. Offbeatness avoids all such cultural referencing because it is defined solely with respect to a pulse, regardless of cultural norms. (Granted, what a pulse is may also be culturally defined, but there is a point at which caveat upon caveat becomes counterproductive.)

Furthermore, in jazz, samba, and reggae (to name just a few examples) this would not qualify as syncopation (in the sense of accents in abnormal or unusual places) because beats other than “the one” are regularly accented in those genres as a matter of course. In the case of folkloric samba, even the placement of accents on the second eighth note, therefore, is not syncopation because at certain places in the rhythmic cycle, that is the normal—expected—pattern of accents for samba, part of the definition of the style. Hence, it does not constitute syncopation if we are to accept the definition of the term as used and cited by Kauffman, Kerman, and Novotney. In other words, “syncopation” is not necessarily the correct term for the phenomenon of accents off the downbeat when it comes to non-European music.

Moreover, in Meter in Music, Hule observes that “[a]ccent, defined as dynamic stress by seventeenth- and eighteenth-century writers, was one of the means of enhancing the perception of meter, but it became predominant only in the last half of the eighteenth century [emphasis added]. The idea that the measure is a pattern of accents is so widely held today that it is difficult to imagine that notation that looks modern does not have regular accentual patterns. Quite a number of serious scholarly studies of this music [European art music of 1600–1800] make this assumption almost unconsciously by translating the (sometimes difficult) early descriptions of meter into equivalent descriptions of the modern accentual measure” [5, p. viii] Thus, it turns out that the current view of rhythm and meter is not natural, or even traditional, let alone global. In fact, in Essential Dictionary of MUSIC NOTATION: The most practical and concise source for music notation is perfect for all musicians—amateur to professional (the actual book title) states that “the preferred/recommended beaming for the 9/8 compound meter is given as three groups of three eighth notes” [6, p. 73]. This goes against the accent pattern implied by the 9/8 meter in Turkish (and other Balkan) music, which is executed as 4+5, 5+4, 2+2+2+3, etc., but rarely 3+3+3. The 9/8 is one of the most common and typical meters in Turkish music, not an atypical curiosity. This passage is included here to demonstrate the dangers in applying western European norms to other musics (as indicated by the phrase “perfect for all musicians”).

[1] Toussaint, G., 2005. Mathematical Features for Recognizing Preference in Sub-Saharan African Traditional Rhythm Timelines. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 3686:18-27. Springer Berlin/Heidelberg, 2005. [2] Novotney, E. D. “The 3-2 Relationship as the Foundation of Timelines in West African Musics,” University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (Ph.D. dissertation), Urbana-Champaign, Illinois, 1998.

[3] Kauffman, R. 1980. African Rhythm: A Reassessment. Ethnomusicology 24 (3):393–415.

[4] Kerman, J., LISTEN: Brief Edition, New York, NY: Worth Publishers, Inc., 1987, p. 20.

[5] Hule, G., Meter in Music, 1600–1800: Performance, Perception, and Notation, Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1999.

[6] Gerou, T., and Lusk, L., Essential Dictionary of MUSIC NOTATION: The most practical and concise source for music notation is perfect for all musicians—amateur to professional, Van Nuys, CA: Alfred Publishing Co., Inc., 1996.

as well as with the rather confusing (to some) third-surdo pattern ….X.X…..XX.X,

as well as with the rather confusing (to some) third-surdo pattern ….X.X…..XX.X,